DETROIT (AP) — Only a couple of weeks after Barack Obama won the presidency in 2008, the man who would become his Republican challenger in the next election penned a New York Times column with a fateful headline: "Let Detroit Go Bankrupt."

Those four words would haunt Mitt Romney across the Rust Belt, where auto manufacturing remains an economic pillar — especially in Ohio, a state that every successful GOP presidential nominee has carried, and in his home state of Michigan, where his father was an auto executive and governor.

Romney's opposition to the federal rescue of General Motors and Chrysler didn't necessarily seal his fate in those two crucial states. But no other issue hung in the background for so long. And nothing that Romney tried — his many visits, the millions spent on ads, his efforts to explain and refine his position — could overcome it.

"The biggest determining factor was that we couldn't handle the automobile bailout issue," said Bob Bennett, chairman of the Ohio Republican Party.

Fairly or not, the perception of Romney as indifferent to the auto industry's fate was "a coffin nail," said John Heitmann, a University of Dayton historian who teaches and writes about the car's place in American culture.

Ohio is second only to Michigan in auto-related employment. A 2010 report by the Center for Automotive Research in Ann Arbor said the industry accounted for more than 848,000 jobs in Ohio, or 12.4 percent of the workforce. That included jobs with vehicle manufacturers or dealers and with businesses that sell products or services to them, plus "spinoff" jobs produced by their economic activity.

Exit polls conducted for The Associated Press and television networks found that about 60 percent of voters in both states supported the government's loan and industry restructuring program, and three-quarters of them backed Obama. The bailout also was popular in Wisconsin, even though it hadn't stopped GM and Chrysler from closing plants there.

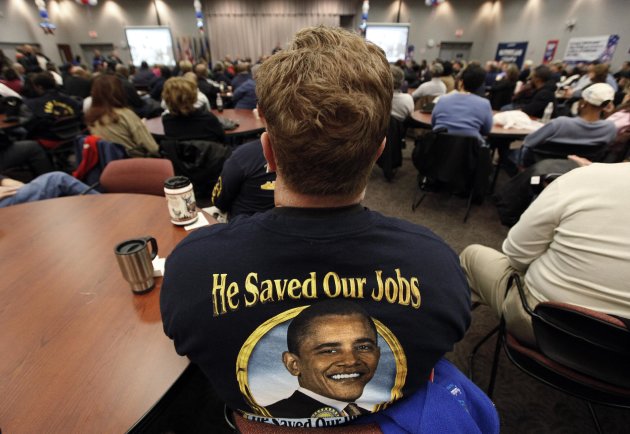

"We have a debt to pay back to President Obama. He saved us," said Joseph Losier, 33, a fourth-generation autoworker from suburban Detroit. After the bailout, Chrysler hired 500 people at the stamping plant where he works.

Even those with no direct connection to the industry were grateful.

"He actually kept his promise. I felt like he cared," said Darlene Jackson, 57, of Detroit, who has worked as a seamstress since losing her city job during the recession.

Romney insisted he'd been misunderstood — he wanted to save U.S. auto manufacturing, not destroy it. In his newspaper column, he argued that federal loans would merely postpone the companies' demise: "You can kiss the American automotive industry goodbye."

He called for a "managed bankruptcy" that would let the companies cut labor costs and become more competitive. Proper roles for government would include supporting energy and technology research, adjusting tax policies and protecting car buyers' warranties, he said.

But those nuances got lost as the campaign geared up. Automakers' fortunes had improved, and as many as 1 million jobs had been saved. Obama said Romney's approach would never have worked because no private capital was available to keep the companies afloat.

After stumbling badly during the first debate, the president made the bailout an early topic during the second. He raised it again during the candidates' final encounter, which was supposed to be about foreign policy.

"If we had taken your advice ... about our auto industry, we'd be buying cars from China instead of selling cars to China," Obama said.

A defensive Romney retorted: "I'm a son of Detroit. ... I would do nothing to hurt the U.S. auto industry."

But by then, the argument was a moot point for most Ohio voters. Nearly seven in 10 had made up their minds before September, the exit polls showed.

With time running out, Romney strategists gambled by airing television and radio ads in Ohio that claimed Obama's policies had led GM and Chrysler to build cars in China. The move backfired, drawing sharp rebukes from both companies.

"It was very misleading, to be kind. It really upset a lot of our people," said Dave Green, president of a United Auto Workers local representing about 1,500 workers at a plant in Lordstown.

Obama won Michigan by a comfortable margin but took Ohio with just over 50 percent of the vote. Despite his steadfast support of organized labor, many blue-collar autoworkers were torn because of disagreements with the president over issues such as guns and abortion, Losier said.

That's where the bailout may have tipped the scales. Union members who backed the president lobbied wavering co-workers, reminding them how dire their situation had been when Obama took office.

"There was a real belief that they were going to liquidate our facility," Green said. "People were walking around with clipboards taking inventory. It did not look good. The polls were all saying, 'Don't rescue the auto companies.' But he did it anyway."

In the end, Green said, the choice came down to a simple question: "Who are we going to vote for — the guy who was trying to push us down the river or the guy who was throwing us a life vest?"

The bailout was popular with independents and even some Republicans, and drew support for Obama outside the usual Democratic-leaning areas, said Chris Redfern, chairman of the Ohio Democratic Party.

Frank Hocker, a retiree who once worked at a truck manufacturing plant in Springfield, said he wasn't a single-issue voter. But when Obama "stuck his neck out and did the right thing with General Motors, you know, that satisfied me."

___

Associated Press writers Justin Pope and Tom Krisher in Detroit and Julie Carr Smith and Ann Sanner in Columbus contributed to this report.

No comments:

Post a Comment