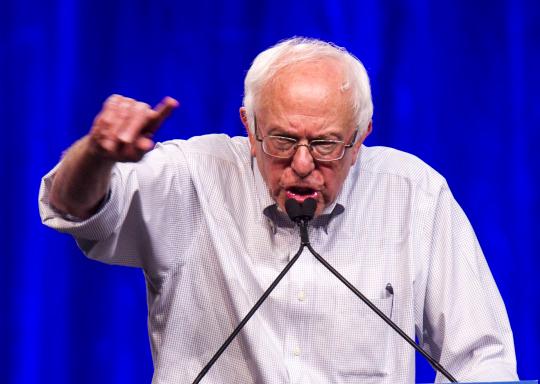

Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders speaks to a sold-out crowd during a campaign event in Los Angeles on Monday. (Photo: Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

LOS ANGELES — On Monday evening I took an Uber from my house in northeast L.A. to the Memorial Sports Arena just south of downtown. Correction: I took the Uber to exit 20A on the 110 South — the off-ramp closest to the Memorial Sports Arena. There were so many cars heading to the venue that the entire right half of the freeway had become a parking lot. It was almost 7 p.m. — start time. I told my driver, Petros, that I was going to have to get out and walk.

Petros looked puzzled.

“Is something going on tonight?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “Bernie Sanders is having a rally.”

Petros still looked puzzled. I set off down the side of the freeway.

I’d come to see Sanders speak out of a sense of professional duty, at least in part. Presidential candidates usually descend on deep blue California for one reason and one reason only: money. They fly in, flutter around a $40,000-per-head celebrity fundraiser at George Clooney’s house and fly out. Actual rallies with actual voters here are rare. As a Los Angeles-based political reporter, I would have been remiss if I had skipped the first big one in years.

But I’ll admit that I was personally curious as well. At first, many in the press had dismissed Sanders, the 73-year-old Vermont senator and self-described democratic socialist whoannounced his presidential ambitions in April, as a cranky, irrelevant gadfly. And yet now, three months later, Sanders was polling at 36 percent in New Hampshire — a mere six points behind Hillary Clinton, the all-but-anointed Democratic nominee. In Iowa he was already attracting a quarter of the vote. And for weeks he’d been touring cities and college towns around the country, attracting audiences several times larger than anything Clinton or her would-be Republican rivals could hope for — even though people like Petros had never heard of him.

What’s going on? What is a huge Bernie Sanders rally actually like in person? And why are so many progressives suddenly so riled up about a career legislator whose hunched shoulders, messy white hair and gruff Brooklyn yawp they’ve spent the last few decades ignoring on C-SPAN?

After trudging through the trash on the shoulder of the 110 and circumnavigating an endless, gated parking lot, I finally arrived at the arena. My initial impression was that I’d been here before. I attended my first political rally when I was a freshman in college — a concert for Ralph Nader at Madison Square Garden. (A cute girl with an extra ticket invited me at the last minute.) I remember a man who was vowing to fast until Nader, then a Green Party candidate, was allowed to debate George W. Bush and Al Gore. I remember stoned undergrads in “Bush and Gore Make Me Wanna Ralph” T-shirts. I remember dyed green hair. I remember multiple piercings. And I remember a lot of older people — baby boomers who might have once been accused of smelling like patchouli but who now looked just like the conservative churchgoers you’d meet at Republican events.

Presidential candidate Ralph Nader speaks at a Green Party rally at Madison Square Garden in New York in October 2000. (Photo: Evan Agostini/ImageDirect via Getty Images)

The line in L.A. was thousands and thousands of people long — it snaked around the block — and stylistically, it seemed pretty similar. The couple who pulled up in a yellow Corolla with a collage of bumper stickers on the back (“Vote Dammit,” “Equality on My Mind,” “Minecraft,” “Cthulhu”) and “Honk 4 Bernie” and “#TakeBackAmerica” written in red marker on their windows. The skinny, middle-aged African-American man in a black Occupy Wall Street T-shirt and a large black hat. The flip-flops. The backward baseball caps. The beards. The crowd was full of college kids from nearby USC; young, progressive professionals; and liberal retirees in loose-fitting Ralph Lauren. Mostly white, but still fairly diverse. Near the entrance there was the usual rally-going array of activists (“Ferguson is everywhere”) and opportunists (“Feel the Bern” buttons for ONLY $5). As I entered the arena, “Turn! Turn! Turn!” by the Byrds was playing on the PA.

Even Sanders’ speech sounded a lot like Nader’s. Back in 2000, Nader also slammed big business for what he called “a corporate crime wave,” accusing both the Democratic and Republican parties of being controlled by corporations. “Our country has been sold to the highest bidder,” Nader said. “We’re going backwards, while the rich are becoming superrich.” He touted his plans for paid parental leave and paid sick leave. He criticized America for failing to join the rest of the developed world in enacting universal health care. And he railed against the criminal justice system, arguing, “The major public housing project in this country is building prison cells.” Afterward, voter Thomas King, then 22, contrasted Nader with that year’s Democratic Senate nominee from New York. “I’m not too pleased with the fact that [Hillary] Clinton and the New Democrats have moved so close to the center,” King told the New York Times. “This is a populist movement.”

Hearing Sanders speak on Monday about an economy that is “rigged … to benefit the people on top,” about how he “can’t be bought” by corporations, about how it “makes a lot more sense to be investing in education than incarceration,” about how it’s an “international embarrassment” that the U.S. doesn’t have “Medicare for all,” and about how his “family values,” unlike the GOP’s, encompass paid leave for parents, I couldn’t help but feel a little déjà vu — even if the crowd roared after every line like they’d never encountered another candidate willing to say these kinds of things.

Sanders supporters cheer at his campaign rally at the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena on Monday. (Photo: Charles Ommanney/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Sanders has real appeal for progressives craving an alternative to Clinton: the dogged consistency, the ambitious policy prescriptions, the rumpled authenticity. All of that came across more clearly on the stump than it ever does on TV.

But Nader was rumpled and authentic, too. That’s why I was more interested Monday in the two big differences on display in Los Angeles between Sanders and his anti-corporate predecessor — not to mention every other major outsider candidate who’s come before, whether conservative (like Ross Perot), libertarian (like Ron Paul) or liberal (like Robert La Follette).

The first difference was the sheer size of the event. As soon as Sanders waddled onstage in Los Angeles, he announced that “more than 27,000” people were in attendance. Such claims are impossible to verify, but the 16,000-seat arena was nearly full, and thousands more were watching in overflow areas outside the venue. The rally looked (and sounded) massive — more like a deafening, ecstatic, slightly drunken rock concert than a fringe political gathering. And the L.A. event wasn’t an isolated incident. Roughly 28,000 people showed up for Sanders’ rally in Portland, Ore., on Sunday. He drew 15,000 in Seattle; 11,000 in Phoenix; 10,000 in Madison, Wis.; 8,000 in Dallas; and 4,500 in New Orleans. All told, Sanders has attracted more than 100,000 people to his campaign events in recent weeks.

That’s completely unprecedented this early in a presidential primary cycle. (The election is still 15 months away.) For comparison’s sake, Clinton’s biggest crowd so far this year was 5,500. There were 15,000 people at the Nader concert I saw in 2000 — but that was three weeks before Election Day. Paul’s storied 2008 and 2012 crowds topped out around 10,000. Sanders is even surpassing Barack Obama’s revolutionary 2008 campaign. In February 2007, Obama drew 20,000 people to Town Lake in Austin, Texas; in April, he attracted 20,000 to an outdoor rally at Yellow Jacket Park in Atlanta; and in September, 24,000 came to see him speak in New York’s Washington Square Park. But Obama rallies didn’t pass the 28,000 mark until 2008.

The second difference on display Monday was what I’ll call the “responsiveness” of Sanders’ campaign. For the first few months after he entered the contest, Sanders largely shied away from issues of racial equality: bias in policing, mass incarceration, voting rights, the treatment of unauthorized immigrants. In July, Sanders, who has always been “all about unions, corporations — basically economic issues rather than cultural ones,” according to an old friend and early political confidant, appeared at Netroots Nation and frustrated civil rights activists when he answered questions about racial issues by pivoting back to economic ones. “Black lives of course matter,” he said defensively after he was interrupted by Black Lives Matter protesters. “If you don’t want me to be here, that’s OK.” Then in Seattle last weekend, another group of Black Lives Matter protesters took the stage and refused to let Sanders speak.

Sanders speaks at the rally at the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena on Monday. (Photo: Ringo H.W. Chiu/AP)

Sanders has a reputation for self-righteousness, and initially he seemed to be sticking to his “it’s a class problem not a race problem” script. But in the weeks since Netroots Nation, something seems to have changed. First, the candidate took a meeting with Symone Sanders (no relation), a young black organizer with the D.C.-based Coalition for Juvenile Justice. He listened to her unsolicited advice on racial issues. Then he offered her a job as his national press secretary. A day after being interrupted in Seattle, the candidate released a sweeping policy platform designed to combat racial inequality. And in Portland and Los Angeles, Symone Sanders debuted as the new public face of the campaign, emceeing each event and introducing her boss to his supporters.

“It’s very important that we say those words: ‘black lives matter,’” Symone Sanders said in L.A. “It’s also important that people in office turn those words into action.”

A few minutes later, Bernie Sanders pledged to do just that. “One year after the death of Michael Brown,” he said from the podium, “there’s no candidate who will fight harder to end institutional racism.”

Ultimately, these two differences — the mind-boggling size of Sanders’ early campaign events and the speed with which he has reshuffled his campaign in response to activists’ concerns — may have less to do with the messenger himself, or his message, than the changing world Sanders is now trying to reach, and the tools he now has at his disposal to reach it.

Nearly eight years ago, I wrote a story for Newsweek about the rise of what some observers were then referring to as “long tail” candidates for president. (The phrase was a reference to the theory, popularized by Wired editor Chris Anderson, that “our economy and culture is shifting from mass markets to million of niches.”) My argument was that we were beginning to see a shift away from the two-sizes-fit-all categories of Democrat and Republican and toward a more personalized, motley politics.

“As the Web allows niche voters to form communities, raise money and get heard,” I wrote, “it’s inevitable that the major-party machines will clash with — and ultimately accommodate — the individualized constituencies they’re struggling to serve.”

The experts I talked to made a couple of predictions. First, that “unlike their predecessors, the next generation of niche politicians won’t necessarily choose the third-party route. Instead, tomorrow’s most successful narrowcasters will likely run as major-party candidates in the primaries, where widely seen debates and easy ballot access will bring exposure and credibility.” Second, while long-tail candidates won’t win the White House anytime soon, “their niche concerns and vocal supporters will demand unprecedented attention” — and mainstream politicians will begin to mine their more marginal counterparts for ideas (and votes).

The sense I got Monday is that the Sanders campaign is the first full realization of this concept. Instagram didn’t exist when Obama launched his presidential campaign in 2007. The iPhone had yet to be released. Twitter still hadn’t taken off. Facebook was a way to connect with your real-life friends — not a global hub for news, marketing and politics.

A supporter takes pictures during the Sanders rally in Los Angeles on Monday. (Photo: Ringo H.W. Chiu/AP)

Since then, social media has permeated every aspect of our lives. It’s become our constant mobile companion. It basicallyis the media at this point — the main way we absorb information about what’s happening in the world. And that, in turn, has amplified the long-tail effect. When every candidate is in your pocket all the time, it’s easier to find the one who seems to speak for you; when your feed is full of friends echoing your political passions, it’s easier to feel like you’re part of something bigger than yourself — a “political revolution,” as Sanders put in Los Angeles. Nothing is fringe; everything feels mainstream. And when activists revolt, a candidate can’t help but hear; every criticism is reposted, regrammed and retweeted until it becomes impossible to ignore.

That’s a big part of the reason why more than 27,000 people showed up to see Sanders speak in Los Angeles: becauseeveryone seemed to be going. And it’s a big part of the reason why Sanders shifted his stance on racial justice so quickly as well: because everyone seemed to be complaining.

As I was leaving the Memorial Sports Arena Monday night, I met a man named Steve Smith. He’d caravanned into the city from Azusa with his wife and four friends. I asked him what he thought of the rally.

“It was absolutely electrifying — like seeing Zeppelin or the Who,” said Smith, 61. “Compare this to Hillary — a couple hundred people with zero enthusiasm. Sanders is the horse to keep your eye on. He’s the only candidate I know who can get huge numbers of the under-25s out to vote. The others don’t stand a chance.”

I was going to ask whether Smith really thought Sanders could upend the system — whether the senator from Vermont could do what Nader, Perot and Paul had failed to do — or whether that was just how it seemed on a warm night in Southern California, surrounded by tens of thousands of hopeful supporters streaming north through Exposition Park. But then I noticed him sniffing the air.

I sniffed too. Somebody was smoking pot.

“A familiar smell!” said Smith. He grinned. “Not bad at all.”

No comments:

Post a Comment